This is part of an ongoing set of one-question emails sent to people we know, or would like to get to know, about things that interest us and inform our collective practice. They’ll be featured on the site weekly, usually on Fridays. These questions are more about unfolding ideas than about the people we’re asking, but we do ask those kinds of questions too.

We’re pleased to continue this project with a question for Caroline Woolard, one of the founders of two incredibly great initiatives, OurGoods.org and Trade School.

How can we not only define, but also enact, a new set of ethics and values that could transform the way we share, organize, and create?

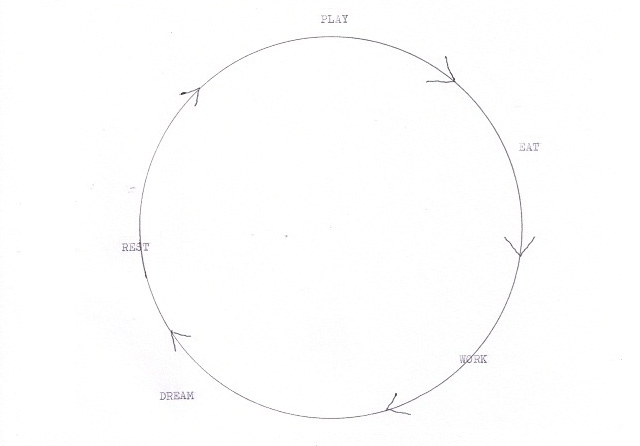

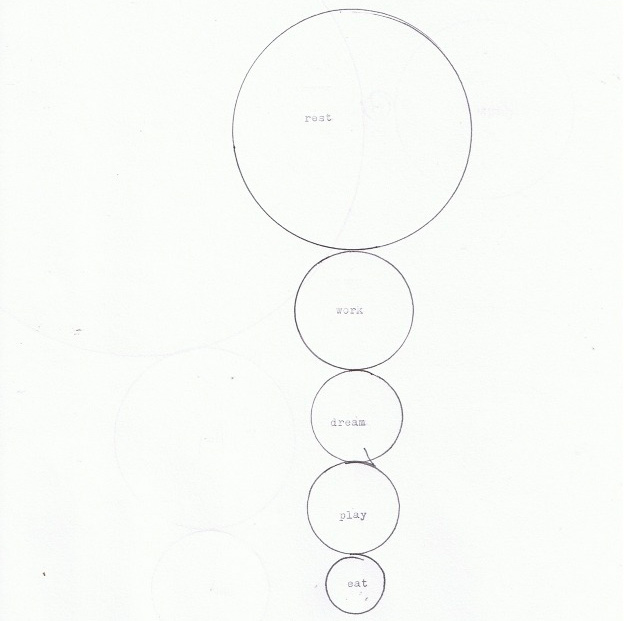

Most people already have curiosity, enthusiasm, and strong desires to speak truth, hone a craft, produce beauty, and connect with others. So I will rephrase the question: How can we practice sharing, organizing, and creating in ways that transform ourselves, our communities, and the world? Here are some ways I do this:

Create online tools for collaboration and exchange!

We are only twenty years into the internet-era. We are in a beautifully experimental stage of the information revolution. Since the internet reached a critical mass in 1990, many people have been asking online platforms to foster deep connections in real time and space. At OurGoods.org, we support the production of new work through barter, because resource sharing is the paradigm of the 21st century. OurGoods is specifically dedicated to the barter of creative skills, spaces, and objects, because we want to build tools for the communities we are part of.

Learn from elders in sharing communities

We are in a contemporary fumbling for sharing rituals at intimate-distance. I’ve been looking to 30-year-old intentional communities and collectively-run spaces and institutions for advice. I’ve been visiting the intentional community Ganas, in NYC, to learn about the relationships they’ve built to share money, cars, houses, and work for over 30 years. At Ganas, for three decades, a voluntary daily meeting is set aside for members to talk through their personal struggles with cooperation. Members of Ganas recognize that no change will happen unless we struggle to “become the change we want to see in the world.” We are conditioned to compete, talk over, and gossip. We need more spaces to practice cooperating, listening, and working through conflict. Jen Abrams, a co-founder of OurGoods, has worked in the oldest collectively-run women and trans theater space for 13 years. She reminds me that, “you have to take time to check in with one another…emotions are not efficient… either you address your feelings together before the meeting, or you end up working through them while trying to have a meeting.”

Vocalize your Values

At Trade School, we asked a facilitator to help us come up with our principles. We talked about why we were each involved in Trade School New York (there are now Trade Schools in over 6 countries) and brainstormed about the things that are at the core of our work (the things that probably won’t ever be changed). After 2 hours, we made this rough set of working principles:

WHAT?

1. Trade School is a learning experiment where teachers barter with students.

2. Trade School is not free– we believe in the power of non-monetary value.

3. We place equal value on big ideas, practical skills, and experiential knowledge.

WHY?

1. Everyone has something to offer.

2. We are actively working to create safe spaces for people and ideas.

3. We want more spaces made by and for the people who use them.

HOW?

1. Trade School runs on mutual respect.

2. We avoid hoarding leadership by sharing responsibilities and information.

3. We are motivated by integrity, not coercion.

4. Our organization is always learning and evolving.

Practice forever

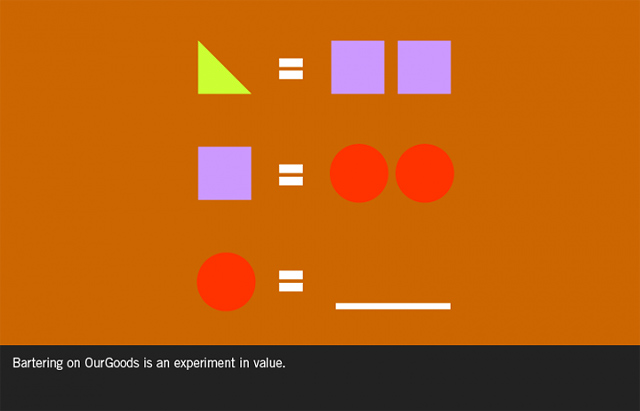

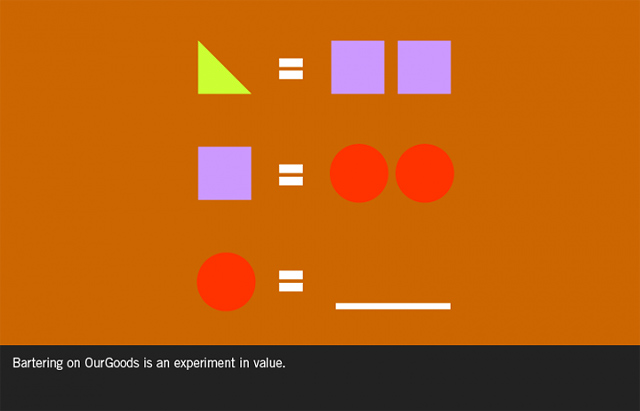

We recognize that bartering is a way to experiment with value. Because value is subjective, some people may not value the work that you make as much as you do. After bartering for years on OurGoods.org, we’ve come up with these basic guidelines:

1. Be clear: Define the exchange. Articulate what constitutes a job well-done.

2. Do your homework: Read your partner’s profile and feedback. Meet before you agree.

3. Be accountable: Do what you said you were going to do, when you said you’d do it.

4. Communicate: Stay in touch. Talk about what’s going right (or wrong) as it happens.

5. Leave feedback: This is what makes our community work.

Caroline Woolard is a Brooklyn based, post-media artist exploring civic engagement and communitarianism. Her work is collaborative and often takes the form of sculptures, websites, and workshops. Woolard is a co-founder of OurGoods.org and Trade School, two barter economies for cultural producers, and a coordinating member of SolidarityNYC, an organization that promotes grassroots economic justice.