Hope you’ve had a chance to check out the epic post Hiba made last week on our show, Archival Tendencies (Lossy Practices), which just wrapped up at Modern Fuel in Kingston, Ontario. For some more background on the show, here’s a re-post of a conversation we had with Christine Dewancker, long-time friend and emerging artist who exhibited in the State of Flux space during the run of Archive Tendencies at Modern Fuel.

You should check out more on Modern Fuel and more on Christine Dewancker and read the full PDF of the interview program!

And now, without further adieu…

A CONVERSATION: Christine Dewancker and Broken City Lab

CD: Maybe a good place to start is talking a little about your project in Kingston and walking through the process of what composes the work. What were the questions you started with in this project?

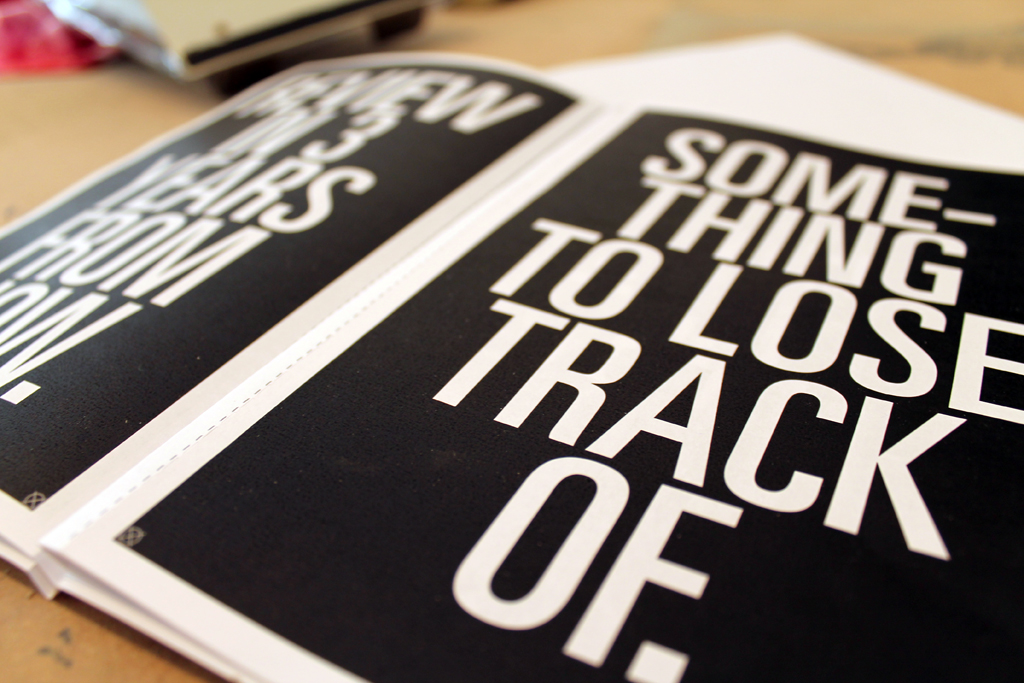

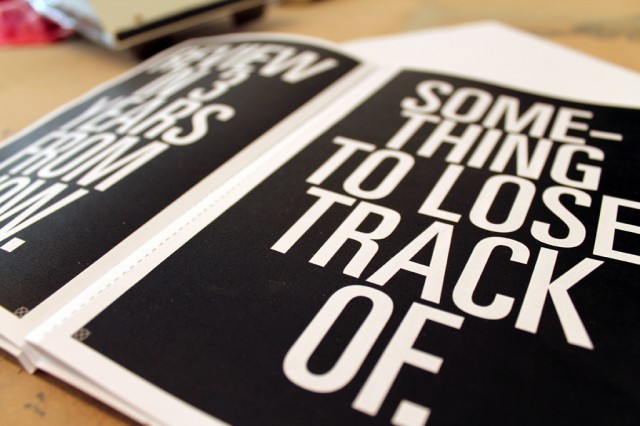

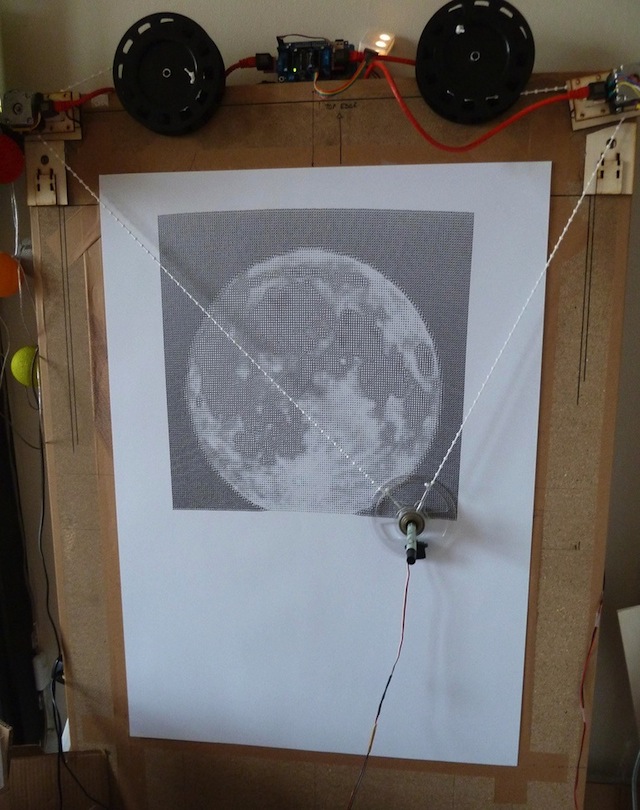

BCL: This exhibition, Archival Tendencies (Lossy Practices), came out of an interest in looking at the idea of bureaucracy as a framing device for the experience of locality. We’ve often looked at the ideas of narratives that are felt and applied to the places where we live, and it seemed like the archive was both a repository and site of production for the narratives of a city. The archive and the practices that embed within the archives both official records and donated ephemera uniquely capture a sense of time and a sense of place. In looking at that idea of the archive as a central site for compiling and maybe even underwriting our collective understanding of a place, whether experienced first-hand or not, it seemed that there was also a way to imagine certain processes that could strain or adjust or disrupt the way an archive would ideally function and the things that would be kept within it. That sensibility is the starting point for all of the work.

CD: I would like to hear some of your thoughts about working through a process that is inherently collaborative; not only in the context of working within a collective, but in the cities and communities Broken City Lab works with. What are some of the concerns you face with the role of “artist(s)” in a “community”?

BCL: The concern that seems rather unshakable is around the imposition an artist might make on the community and the effects of that imposition that may be beyond the view the artist might have for a particular project. The severity of that imposition can be mitigated, slowly and gradually, by longer-term commitments. In situations wherein that timeframe is impossible or at least impractical, it becomes more challenging to negotiate the expectations we have as artists for the places in which we work and in turn, the expectations that are placed on us. While earlier on, we would try to recreate elements of our practice in other places, we’ve shifted towards trying to create projects that have entry-points that are not contingent on our long-term engagement with the places in which they’re located. This exhibition is a good example — while we visited the Kingston archives, and although we had considered trying to find ways to animate histories that seemed rather specific to the city (such as the penitentiary and the economies around it), we ultimately settled on trying to develop a set of works that could point towards a set of possibilities and implications embedded in the expressions of power found in both official and unofficial archival practices, while playing with a range of efforts to both earnestly “keep track of” and intentionally “lose sight of” a set of artifacts and ideas that are normally discarded, pushed aside, or otherwise forgotten.

CD: I do want to make a point to discuss the multiple hats the collective wears on any given project; these range anywhere from design consultant, community organizer, graphic designer, urban planner, social analyst to teacher to name a few. While moving fluidly between these ‘positions’ we’ll call them, you continue to keep a foot (or toe) in the art world in the ways you choose to approach and present your work. I would like to hear your thoughts on how this opens up possibilities for new ideas/social change/reform.

BCL: That fluidity is absolutely an ongoing point of interest, but it’s become more and more complicated as the things that we’ve articulated as a part of our practice become more legible and in turn more readily instrumentalized. On one hand, it allows for opportunities to look at the possibility for social change in new formations. It gives us an opportunity to partner on larger scale projects that can in turn have a larger (measured and/or measurable) impact, and those projects can draw resources into projects in really interesting ways. On the other hand, the multiplicity of these positions, or roles, or hats, can draw our work into arenas that are less interesting for us — the act of measurement for example. The relationship that we’re interested in maintaining with the art world is based on the belief in art as a site of continual and infinite possibility in articulating different ways to be in the world.

CD: What function does maintaining an artistic approach serve in your work that bridges so many disciplines? I really like a quote by Nato Thompson which is a little overstated but essentially what I am getting at with my question here: “…art is about the impossible-the impossible that is necessary because the pragmatic is failing.” I am pulling that quote by Thompson out of its original context which I’d like to do due diligence to here and discuss a little with you. The quote is from a conversation he had with artist Martha Rosler in which they were discussing the alignment of artists/ role of art within social movements. Mentioned specifically was the Occupy Movement and the deeply held belief in resistance and reform that the movement embodies- which is absolutely present in many of the practices of artists and collectives working today. I am curious how some of these ideas (art/activism, art as activism) resonate with you and the work of BCL.

BCL: The relationship between art and activism has been presented and imagined in more or less interesting configurations, though it would seem that the very thing that art can bring to something like activism (that is, a sense of infinite possibility) is the very thing that can get lost when activism is brought into art. Activism, at least in its general framing up until Occupy, seemed very interested in accomplishing something, even if that accomplishment was built on the refusal of something else. Art can offer the potential to not do anything, and yet its very existence can do something to us, it’s just not always measurable. This immeasurability, this sense of escape from perhaps a rather neoliberal tendency to have goals in the first place, is precisely what makes art so important.

CD: I’d like to shift the questions back to where you work out of primarily- Windsor Ontario. I remember you described the initial BCL meetings were held in your apartment and you functioned as an ad-hoc collective in 2008. Now you are operating out of a storefront space in downtown Windsor and supported by the Trillium Foundation. What this has enabled in your programming?

BCL: CIVIC SPACE was envisioned and funded a two-year project, and so the programming we’ve engaged at that storefront operates at a different scale than the work we’ve done in the past, insofar as it gives a sustained arc to the conversation we’re trying to cultivate. It gives us a larger meeting space than an apartment to be sure, but it also adds new layers of complexity to what it is we try to do. The programming itself occurs at various paces — monthly residencies or exhibitions, weekend-long events, day-long workshops — but because we know that there is an end-date, we’re interested in trying to keep the programming as responsive as we can. The very idea of thinking about any kind of sustained programming, however, is a much different conversation than we were having in 2008.

CD: In addition to your own projects, BCL initiates and is involved with a host of other activities; from artist residencies to workshops and an upcoming conference (second year running). This may seem like a broad question but I’d like to get at the position you see BCL occupying as both producer and facilitator within a city like Windsor. Can you describe how your role has changed (and is changing) within the cultural landscape of the city?

BCL: As we take on new projects, we seem to be continually moving towards these larger production or facilitation-based roles, and for the most part, it feels like an appropriate fit. Given the history of our practice, and in particular, its relationship to the context of Windsor, we’ve been able to find new avenues and partnerships to try to make a case for Windsor to consider a different relationship with art and artists. In particular, partnering with the Arts Council Windsor & Region and the City of Windsor for Neighbourhood Spaces, a residency which brings artists into community spaces across the Windsor-Essex area, or Mobile Frames, which in partnership with Media City, Common Ground, and SB Contemporary will bring internationally renowned filmmakers into Windsor for longer-term research and production residencies, feel like great examples of this idea of cultivating new and different relationships. Our role continues to change, and will change even more as CIVIC SPACE wraps up next spring, but projects like the ones mentioned above, which pull together new partnerships with the support the transformative resources from the Ontario Trillium Foundation, make our role feel a lot less important in making things like this happen, and that’s a really good thing.